Holt’s Matrimonial Agency provided a matchmaker service to turn-of-the-century Melbourne. It was also the place, for a quickie wedding.

Melbourne in the 1880s, was boom town.

The gold rush that kicked off in 1852 had been followed by a period of high agricultural prices, which had turned the city into an economic powerhouse. The International Exhibition of 1880 had raised Melbourne’s profile, new buildings sprung up on every street, while the newly rich enjoyed their wealth in the city’s many fine hotels.

For a time, Melbourne was the world’s wealthiest city, after London.

This is the era known as ‘Marvellous Melbourne’.

Among the city’s many aspiring residents were Annie and James Holt, a young married couple with an entrepreneurial zeal.

Annie Holt’s background was modest. From a broken home, and lacking formal education, as a young woman she worked menial jobs, often as a maid or housekeeper. But this background also provided an opportunity.

Melbourne’s many wealthy residents were always in need of good domestic help, the Holts started a servant’s agency to cater to this need. Servants would register with the Holts, who would then place them into households who required their particular skills.

Starting in the early 1880s, alongside the city’s boom period, the Holts new business proved successful.

But as the registry grew, Annie noticed something in relation to the female servants she placed:

‘Sometimes an elderly man, generally a widower, would require a housekeeper. And I found that very often, if he was satisfied with the housekeeper, he would marry her.

This happened so frequently that the idea of a marriage agency, seemed to me to be an institution that would fill a long felt want.’

– Annie Holt, interviewed in ‘Punch’ magazine, 1894

And so the Holts changed their line, transforming from a servant’s agency, to a matrimonial one. Marvellous Melbourne was full of eligible bachelors, and the Holts would help find them a suitable wife.

Holt’s Matrimonial Agency opened in 1886. James took care of the business side, and left the matchmaking to Annie.

She gave an outline of her method, in the press:

‘A client, a gentleman (or lady), comes to me, states his circumstances, means, position, and verifies his statement to my satisfaction. Either by documentary evidence, or otherwise.

I speak to such of my clients as I think eligible, and confer with the gentleman. I give particulars to both sides, but names are never mentioned. There is no submitting of portraits.

When there appears to be the prospect of mutual suitability, I introduce the parties here (at the agency). If at first interview, the parties find each other agreeable, the acquaintance may be continued.

I do not, in any way, force the courtship.’

– Annie Holt

The fee charged for this introductory service was 1 guinea.

But if a match were to prove successful, the Holts would levy a higher amount, usually equivalent to a fortnight of the couple’s combined income. The higher fee was only payable after the pair had wed.

Some clients were so pleased they even paid extra: one happy groom left the Holts a substantial estate in India, after his death.

Annie Holt showed a remarkable facility for selecting suitable partners. Business boomed.

In 1894, the Holt’s moved the agency to a grander location.

Their new place of business would be a custom built, two storey mansion at 448 Queen Street, opposite the Queen Vic Markets and the remainder of the city’s first cemetery. Reflecting the Holts success, the new premises was spacious and opulent, tastefully decorated by Annie herself.

The agency had expanded in other ways as well.

The new building included a chapel, and the Holts retained clergy on their payroll. They now offered a new service: for ten shillings and sixpence, they would supply rings, witnesses (often the Holts themselves), and a priest, and marry couples on site.

A quickie marriage at Holt’s would often come at the end of a big night on the town, and they were not choosy about who they wed:

‘(It was not) an obstacle to marriage if one, or both, parties were so drunk they could hardly stand up.

Many a pair who’d only just met would end their evening’s spree by getting spliced at Holt’s, and consummating their union in the old cemetery across the road.’

– Robyn Annear, ‘Adrift in Melbourne’

The new wedding service also proved enormously popular: the Holts performed around 1 000 weddings a year.

But Melbourne society in this period was relatively chaste, and these activities stirred up controversy.

Holt’s Matrimonial Agency was frequently denounced in the press as a public nuisance, a moral outrage, and as den of vice and corruption. They also found themselves in trouble with the police.

Under the laws of the day, women under the age of 21 were required to have written permission from a parent or guardian before they wed. A provision often ignored by the Holt’s.

Charges were considered against them several times, but their defense was simple: they testified that they thought the women in question were of age, and had not thought to ask for identification.

Each time the charges were dropped.

The Holts were also implicated in several cases of bigamy: marrying a client who was already married elsewhere. In one well publicised case, the multiply-married groom defended himself in court by stating, ‘under the influence of drink, (he) forgot he was already married.’

The jury acquitted the bigamist. The judge called Holt’s, ‘a blight on this community,’ but they also escaped penalty.

With the agency’s wedding service gaining a seedy reputation, the Holts found difficulty engaging clergy willing to perform the ceremonies. They often had to rely on priests who were themselves in bad standing.

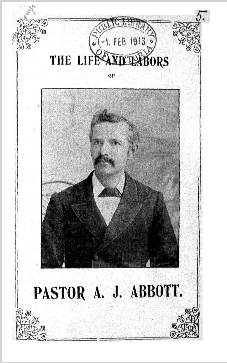

One of their regulars was Reverend Albert J. Abbott, a pastor of the Free Christian Church in Collingwood.

Reverend Abbott was young for a priest, strikingly handsome, and perpetually dogged by controversy. Among other infractions he was accused of fraud, theft, and sexual impropriety with a number of young women.

Abbott was so polarising, the members of his church in Collingwood eventually held a public meeting, to call him to account. In front of a crowd of several hundred, his accusers outlined the charges against him, while Abbott vigorously defended himself.

The outcome: the congregation split in two. Abbott’s opponents subsequently left, to form their own church.

Shortly after this, Abbott began working for the Holts, and took to his new role with vigour.

Unsurprisingly, he was soon accused of knowingly marrying underage girls and bigamists, for a fee. Abbott again refuted the charges, and defended his reputation in the press.

He was never formally charged with any crime.

But his reputation was notorious. While delivering a religious service at a Melbourne Temperance Hall in 1906, he was set upon by an outraged member of the public. Rebecca Haldane jumped on stage and attacked him with an umbrella, accusing him of having performed a bigamous marriage involving her husband.

Haldane was later fined five shillings for assault.

While the Holts had an uneasy relationship with the local authorities, they were also called on, on one occasion, to provide assistance. In October 1891, in one of Melbourne’s most unusual unsolved crimes, the Victorian Parliamentary mace went missing.

The mace is a ceremonial object: a painted black rod, 1.5 metres long, made out of solid silver, and decorated with gold. It is carried into Parliament to commence each session, and out again at the conclusion; a tradition inherited from British Parliament.

Between times it is locked away.

At 1am, on October 9, 1891, officials secured the mace in its storage cupboard at the conclusion of the day’s Parliamentary session. When they went to retrieve it the next day, they were astonished to find the lock had been forced, and the mace stolen.

A minor scandal erupted.

Suspicion settled initially on a handyman, seen leaving Parliament with a suspiciously large package. But the man protested his innocence, and a search of his premises turned up nothing.

In the absence of other suspects, the press floated a lurid theory.

Boccaccio House was a well-known Melbourne brothel, in the ‘Little Lon’ slum area, close to Parliament.

It had long been rumoured that a number of MPs were among the brothel’s clients; it had even been suggested that prostitutes had been brought into Parliament, for afterhours carousing. The press now speculated that during one of these debauches, a light fingered call girl had made off with the mace.

No evidence was found to prove this either, and the owner of the brothel, Annie Wilson, claimed she had no knowledge of the incident. But the tale established itself, and settled into local folklore.

The original mace was never found.

A replacement mace was now required.

Alongside his business interests, James Holt was also a skilled metalworker, a rather specialised trade in early Melbourne. From his basement workshop, he made decorative items in wrought metal: sculptures of animals and trees, and homewares, which he sold on the side.

He also supplied local churches, somewhat ironically, with ecclesiastical equipment, including chalices, and metal staffs.

The authorities now approached Holt, and asked him to create a new Parliamentary mace, a replica of the one that had gone missing. This was completed later in 1891.

Holt’s mace is the one still used, in Victoria’s Parliament today.

Holt’s Matrimonial Agency slowly declined in popularity through the first decade of the 20th century. It’s reputation finally caught up with it, and earnest bachelors sought out less notorious matchmaking providers.

But it proved surprisingly resilient.

The Holts kept the agency, and wedding service, going right through the First World War. In 1925, they finally sold the Queen Street premises, and retired. The mansion and chapel were eventually demolished.

Modest retail premises make up this part of Queen Street today.

Reverend Abbott would continue his enthusiastic nuptial work.

In a pamphlet published by his supporters, it was claimed he had presided over more weddings than any other priest in Australia, performing an average of 80 ceremonies per month. He also ran a successful phrenology business, analysing the shape of his client’s skulls.

Always controversial, Abbott’s enthusiasm also endeared him to people, willing to overlook the claims against him.

Reverend Abbott died in Melbourne, in May 1941.

Fascinating stuff! My 2x great-grandparents were married at Holts’ in 1901, the family always wondered how they met, as one lived at Longwood in Northern Victoria and the other at Outtrim in South Gippsland – quite a distance! It all makes sense now. Regardless, they had a happy marriage and produced 13 wonderful children.

What a great story, that you for sharing that!

A truly fascinating article, but…

Please learn how to use apostrophes!

The plural of for more than one Hart is Harts, not Hart’s. The possessive for one Hart is Hart’s; for two or more it’s Harts’. It’s really that hard!

But I love your site and the wonders you uncover. Keep digging!