When the Australian National Gallery spent $1 million on Jackson Pollock’s ‘Blue Poles’ in 1973, controversy erupted. It now looks like a bargain.

A national art gallery in Canberra was a long time coming.

The idea was first mooted shortly after Federation, when leading Australian artist Tom Roberts began lobbying political leaders. In 1910, Prime Minister Andrew Fisher responded by establishing the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board (CAAB). They were initially charged with acquiring artistic works, of significance to Australia.

In 1912, the committee proposed a national gallery to house their collection. In the meantime, they would be displayed in Government offices.

But trying to advance the National Gallery proved difficult.

The outbreak of World War I delayed the initial proposal. Subsequent governments were preoccupied by the Great Depression, then World War II. An art gallery seemed trivial, by comparison.

Another issue was settling on a location.

When the National Gallery was first proposed, Canberra was still a city under construction. Australia’s Federal Parliament initially sat in Melbourne, and would not move to Canberra until 1927.

While the city had been built to a master plan devised by Chief Architect Walter Burley Griffin, some elements were not fully settled. The proposed gallery was one of these, and several locations were suggested.

The proposal was revived by Harold Holt, in 1967. This was part of a wider push to finish Canberra’s principal buildings, which would also lead to a new High Court and Parliament House.

Holt died in office (you can read about this here), but the gallery continued to inch its way towards existence.

In 1972, it received a boost with the election of Gough Whitlam.

Whitlam’s Labor Party was reform minded, and had an ambitious agenda to change many aspects of Australian life. While the National Gallery was only a small part of this platform, Whitlam, a patron of the arts, was determined to move this forward as well.

Whitlam would work closely with the National Gallery’s provisional director, James Mollison.

Mollison was a former teacher who had followed his interests into a career in the arts. He served as the director of the Ballarat Fine Arts Gallery, before making his way to Canberra, joining CAAB in 1968, and advising the Prime Minister’s office from 1970.

Mollison’s chief responsibility was to oversee the acquisition of new works for the gallery. To date, only Australian art had been considered, but Whitlam encouraged Mollison to be ambitious, and to see what notable international pieces might be attainable.

Ben Heller was a New York art collector with a sharp eye for new talent. In the early 1950s, he had become friends with Jackson Pollock, then still largely unknown.

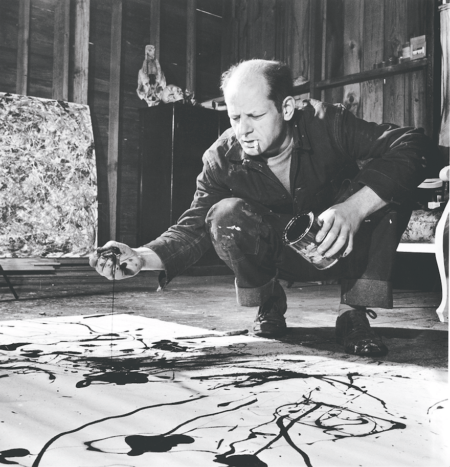

Pollock was a difficult man; in the words of art historian Hugh Honour, ‘raw, violent, consumed by neuroses.’ Frustrated by his inability to master traditional painting techniques, Pollock channelled his turbulent personality into innovation.

From 1947, he began creating large scale canvasses using an unusual technique. Placing the canvas on the floor, he would stand over it and ‘drip’ paint onto the surface, sometimes augmenting this by splattering additional material onto it.

The strange, chaotic artworks this approach produced caused bafflement when they were first revealed. They were impassioned and often colourful, but also shapeless and messy, like the work of a child. Critics were initially dismissive.

But Heller was struck by the unusual paintings.

He bought his first, titled ‘One’, from Pollock in 1950, for $8 000. It was the first major piece the artist had sold in his new style, and cemented the friendship between the two.

Art critics slowly began to respond more positively.

The initial critique at the lack of formal technique, gave way to excitement. This was raw Id captured in paint, and often provoked a strong, emotional reaction. They coined a new term for the style, also applied to the work of William De Koening: Abstract Expressionism.

Pollock painted ‘Blue Poles’, originally titled ‘# 11’, in 1952.

The piece was on an epic scale; two metres high, and four wide. The centre of the canvas was done using the drip technique, mostly utilising yellow, white and orange paint, overlayed with the dark blue slashes that gave the work its final name.

As with all of Pollock’s work, he laboured over the painting for some time, obsessively layering in detail.

Jackson Pollock died in a car accident in 1956, aged only 44. After his death, his work began to climb significantly in value.

Heller purchased ‘Blue Poles’ in 1957 for $32 000, from another collector. He hung it on the wall of his Central Park apartment, where it joined other works from famous modernist artists.

He frequently leant the work to galleries around the world for public display, and it was so large that his living room window had to be removed to get the painting in and out. The removal company, Santini Brothers, cordoned off the street below while they were moving it.

In 1973, Mollison was alerted by his contacts in the art world that Heller may be willing to sell ‘Blue Poles’.

Heller believed that significant art works should not remain in private hands, and regularly sold items from his collection to public institutions. He was also intrigued at the idea of selling it to an Australian gallery, rather than his usual clientele in the US.

But a sticking point would be the price.

Jackson Pollock’s reputation had continued to grow, his paintings now much sought after. Heller, though willing to sell, wanted to use the funds to provide for his family.

He asked for $1.3 million (in Australian dollars).

Mollison had a budget to acquire art at his own discretion, but this was capped at $1 million, for any single work. Approval to go beyond this threshold had to come from the Prime Minister himself.

Mollison made the case for purchasing ‘Blue Poles’ to Whitlam, who approved both the purchase and the price. The National Gallery was a significant undertaking, both men agreed that a showcase central artwork was required.

The sale was completed later in 1973, and plans made to deliver the painting to Canberra the following year. At the time, it was the highest price ever paid both for an American artwork, and a ‘modernist’ work.

In the spirit of transparency, Whitlam decided the price should be made public.

A fiery controversy erupted.

Whitlam’s election victory in 1972 had ended 23 years of conservative rule in Australia.

Though popular, Whitlam was intellectual, with sophisticated tastes, and his policy agenda would be expensive to implement. Still smarting from their electoral defeat, his political opponents sought to portray the new Prime Minister as out of touch with everyday Australians, and fiscally irresponsible.

‘Blue Poles’ seemed to provide them with the means to do both.

The conservative aligned Confederation of Industry called the purchase, ‘a scandalous waste of public money, illustrating the government’s lack of commitment to budgetary restraint.’

The million dollar price tag was labelled ‘outrageous’ and ‘obscene’, by conservative politicians.

Liberal Senator C.L. Laucke even speculated that the naïve Mollison had been conned by ‘sharpies’ in New York. How could this ‘childish’ painting be worth so much money?

A rumour circulated that Pollock had, at best, co-created ‘Blue Poles’.

Writer Stanley Friedman claimed in an article that Pollock had gotten drunk and painted the picture with two friends, the group treading on it in their bare feet and smearing the canvas with alcohol, and even blood.

Pollock’s widow, Lee Kransberg, dismissed the story as ‘100% false’, but it was still cited in Australian Parliament during debate on the purchase. A tabloid newspaper headline screamed:

‘BAREFOOT DRUNKS PAINTED OUR “MASTERPIECE” ‘

‘Blue Poles’ also divided Australia’s art community.

Recent Archibald prize winner Herny Hanke was opposed, and said he ‘did not think much of paintings created with dripped paint.’ Fellow artist Sali Herman agreed, and said, ‘the whole thing stinks. It seems they have money to give away.’

But legendary Australian artist Russel Drysdale, one of the country’s most respected painters, voiced his approval.

‘The whole art world was effected by Pollock and this is one of his masterpieces.

It is priceless.’

– Russell Drysdale

Part of the issue seemed to stem from the abstract nature of the painting, and its unusual composition. Mollison toured the country and ran public information sessions, to try and provide context to the work and its place in art history.

‘Never had such a picture moved and disturbed the Australian public.’

– Patrick McCaughey, art historian and future NGV director

People were interested and the sessions well attended. The painting remained a hot topic.

Despite the controversy, the purchase went ahead.

‘Blue Poles’ was brought to Sydney in a shipping container by boat, arriving in April 1974.

It would be hung in the Art Gallery NSW until the National Gallery was completed. The Federal Government was keen to protect its expensive purchase; the work was kept under a three person, round the clock armed guard.

When it went on display in Sydney, huge crowds turned out to see it.

The National Gallery took several more years to build, finally opening to the public in 1982.

James Mollison oversaw several more controversial acquisitions, most notably another abstract expressionist work: ‘Woman V’ by William de Kooning, (which cost a paltry $650 000 in comparison). He remained director of the gallery until 1989, his tenure widely regarded as successful.

Although the controversy surrounding ‘Blue Poles’ never fully receded.

In the late 1990s, the Howard Government moved forward with another long considered public building: a new National Museum in Canberra.

The design included a garden, ‘The Garden of Australian Dreams’, that would feature artworks showcasing elements of Australian history. Among these, a series of Blue Poles, as a nod to our most famous artwork.

Viewing the plans, the Prime Minister’s office allegedly demanded that this part of the garden be removed.

As of 2016, ‘Blue Poles’ was valued at $350 million.