The origins of Christmas are a surprising grab bag from different cultures, stretching back thousands of years. Here are the roots of the best known Christmas traditions.

Saturnalia and December 25

Before Christmas there was ‘Saturnalia’, a celebration of the Roman god Saturn.

Saturn was an important and complex figure in Roman mythology. Primarily the god of agriculture, he was also the father of Jupiter, and associated with time, and renewal.

Saturn’s importance was marked with an annual festival, ‘Saturnalia’, which was held in December to mark the end of the winter sowing season. Originally a one day celebration on December 17, over time the festival stretched to several days, and then a week.

Saturnalia would climax with an animal sacrifice and feasting on December 25, which made that date one of the most significant across Roman controlled Europe.

In an interesting precursor to Santa, Saturn was also often depicted crossing the skies in a flying chariot.

Holidays, Gift Giving and Lights

Saturnalia included holidays, to reward the hard work of the sowing season.

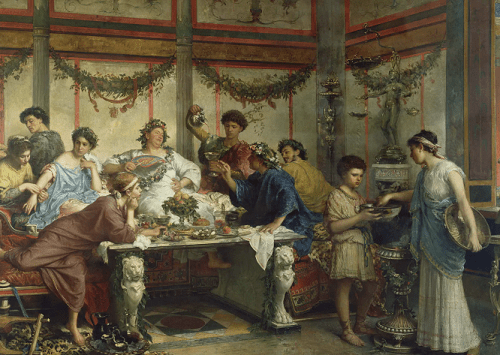

The festival itself had a carnival atmosphere. There were street parties and public feasts (pictured), music, dancing and revelry. Its proximity to the end of the year created an optimistic mood, as people looked to the future.

Lights were an important part of the festivities. The winter solstice occurred around the same time, candles and lamps were lit to signify the approach of longer days, ‘the return of the unconquered sun’.

Another tradition was the exchange of small gifts, in keeping with the celebratory tone. Houses and public spaces would be illuminated, and candles often given as Saturnalia presents.

Christ’s Birthday

Before the 4th century, Christians had not usually celebrated Christ’s birthday. The Bible provides a lot of detail about the event, but excludes a date; when Christ may have been born was not seriously considered until two centuries after his death.

In the 2nd century CE, some Christians began to celebrate Christ’s birthday on January 6. Why this date was chosen, is unclear.

The Roman Emperor Constantine, who ruled between 324 and 337 CE, was the first Roman leader to convert to Christianity.

Constantine’s rise was bloody, and involved a series of conflicts against other aspirants to the throne. Once in power, he attributed his success to his conversion, and made Christianity the official state religion.

This meant abandoning Roman polytheism, with its many Gods, and replacing it with a single Christian God.

To help entrench Christianity, and erase beliefs now considered pagan, Constantine simply co-opted some existing religious traditions. December 25, the climax of Saturnalia and one of the most popular days in the calendar, would still be observed, only now as ‘Christ Mass’: a celebration of the Christ.

Christ Mass was officially proclaimed Christ’s birthday by the Pope in 336. Gift giving, feasting, and displays of lights would remain.

As Christ Mass began to take hold in Western Europe, most Christians shifted the celebration of Christ’s birth to December 25. But some resisted the change, and continued to celebrate on January 6; to this day, this remains the official date of Christmas in Armenia.

Christian communities who changed to December 25 still commemorated January 6 with the ‘Feast of the Epiphany’. The number of days between the two dates gave rise to the phrase ‘the twelve days of Christmas.’

Christmas Trees

December 24, Christmas Eve, was for a long time not just the day before Christmas, but a significant day in its own right. In central Europe, the ‘Feast of Adam and Eve’ was held on this date.

Central to this event was a ‘Paradise Tree’; an evergreen meant to symbolise the tree in the Garden of Eden.

Paradise Trees, usually a fir or pine, would be set up in the homes of Christians as part of their December celebrations. This was especially popular in western Germany.

The trees were decorated with wafers, as a symbol of the eucharist. Later, the decorations became more elaborate, often featuring biscuits, candles and trinkets. The proximity of the feast day to Christmas, lead to the trees being dubbed: Christmas Trees.

Immigrants spread Christmas trees across Europe and America, but by the 19th century their use was still not common outside of Germany.

In February 1840, England’s Queen Victoria married her first cousin Albert, the German Prince of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Albert brought many new traditions with him to England.

Among these: Christmas trees, which became part of the royal household’s holiday celebration.

While Albert was not initially popular with the British public, who viewed him as an outsider, interest in the couple was enormous. Every public appearance was covered exhaustively, everything they did was analysed and discussed.

In December 1848, the royal couple were depicted in a Christmas illustration produced by the London Evening News. This showed a charming domestic scene; Victoria and Albert with their children, standing around a beautifully decorated Christmas Tree.

The image was popular, and widely reproduced. Christmas Trees, previously a novelty, were instantly established as a key Christmas tradition, and spread throughout the British Empire.

Tinsel and the Legend of the Christmas Spider

Tinsel was also popular in Germany, and was another tradition brought to England by Prince Albert. The decoration had been used in Germany since the 17th century, and in Albert’s time was the preserve of well off families; it was made from strips of actual silver plate.

But its origin was more modest.

In several European countries – notably Germany, Poland and the Ukraine – there is a folk tale of a poor peasant widow, unable to afford presents for her young children. The family plant a pinecone which grows into a Christmas Tree, but they are too poor even to be able to decorate that.

On Christmas morning, they wake to find that spiders have spun webs across their tree; when the sun’s rays hit them, they sparkle like decorations.

This well-known story inspired imitation: coloured strings of metal, or metallic fabric, were placed on Christmas Trees to replicate the spider’s webs.

While modern tinsel is made of foil and is found all over the world, in many European countries decorative spiders still adorn Christmas Trees.

Christmas Crackers

Another tradition whose origin can be traced to Victorian England is Christmas Crackers. When I was a child I often wondered why these were also known as ‘Bon Bons’: it turns out they originally were made by a confectioner.

Tom Smith was an English sweet maker who ran a successful shop in London in the 1850s. Christmas was good for business, and Smith produced a series of products specifically for the holiday.

Among these: a sugared almond Bon Bon, that he sold in a twisted paper wrapper. These became popular as a small gift, to increase their appeal Smith began including other items with them: love poems, small toys, and, eventually, jokes and paper hats.

The snapping ‘bang’ sound that gave the item their final name, ‘crackers’, Smith added as a humourous note. Supposedly he was inspired by listening to the pop of wood burning in his fire.

Similar to Christmas trees, the reach of the British Empire in the 19th century ensured Christmas Crackers found a worldwide audience.

Tom Smith’s company still holds the royal warrant, as official suppliers to the royal family for crackers and wrapping paper.

Christmas Cards

Until the 19th century, one of the traditions of Christmas was to write your friends and loved ones a letter, wishing them the best for the season.

Sir Henry Cole, a reform minded British public servant, was one of many in the habit of doing so. But in 1843, finding himself overloaded with work, Cole came up with a clever time saving idea: he would send his acquaintances a card, instead.

Cole commissioned John Calcott Horsley, a fellow member of the Royal Academy, to design the card for him. The front of Horsely’s card showed a multigenerational family, gathered around Christmas dinner, raising a toast to the viewer.

Cole had 1 000 of the cards printed in black and white, the images were then coloured by hand. He wrote a short message inside for each recipient; cards that were surplus to his needs were sold to the public for one shilling, which paid for the entire exercise.

Cole’s ‘Christmas Cards’ were well received by his friends, but drew some criticism.

Several newspapers denounced the use of alcohol in the card’s image, claiming it promoted drunkenness. But the idea of Christmas Cards caught on quickly with the public, and within a decade they were established as another holiday tradition.

Only one unused card remains from Coles original printing: it is kept in the Hallmark Historical museum, in Kansas City.

Santa Claus

Santa Claus is not, as is often claimed, an invention of the Coca Cola company (although he has been used extensively, to sell Coke at Christmas). It is perhaps unsurprising that the figure’s history is more complex.

Santa’s roots can be traced to Nicholas, a devout Christian who became the Bishop of Myra, in modern day Turkey, in the 4th century.

Little is known of Nicholas’ life, as most of the writings about him came hundreds of years after his death. But the traditional story has him as particularly kind to children and the poor, and famously generous; from a wealthy household, on the death of his parents he gave his entire inheritance to charity.

He would also anonymously give gifts to members of his community who were in need.

Nicholas died on December 6, 343 CE. His tomb was later said to excrete a liquid substance, that had healing properties. It became an important pilgrimage site for European Christians, who also venerated relics said to have come from Nicholas’ body.

The many miracles attributed to him, lead to his canonisation as Saint Nicholas. December 6 was marked with a feast in his honour, in which gifts were exchanged.

After the Protestant Reformation, veneration of Saint Nicholas, and other Christian Saints, began to decline across Europe. The one exception was the Netherlands, where the feast of Saint Nicholas continued to be celebrated.

In that country, he was referred to as ‘Sinterklaus.’ Dutch settlers carried this tradition with them to America in the 17th century, where the name was translated into English as ‘Santa Claus’.

Other aspects of modern Santa can also be traced to America.

Scandinavian settlers brought with them folk tales of a wizard, who rewarded good children and punished bad. Saint Nicholas’ association with children meant these were eventually added to the Santa Claus story.

In the 19th century, the proximity of Saint Nicholas’s feast day to Christmas, each with a parallel tradition of gift giving, meant the two celebrations gradually merged. Although some Orthodox Christians continued to celebrate December 6, and still do, and exchange gifts on that date.

On December 23, 1823, the New York ‘Sentinel’ published ‘Account of a Visit From St Nicholas’, a Christmas themed poem that later came to be known as ‘The Night Before Christmas’.

Likely written by Clement Clarke Moore, the poem added a number of elements to Santa; he is large and jolly, and rides in a flying sleigh pulled by 8 reindeer, loaded with a sack of presents which he climbs down chimneys to deliver.

The poem was widely reprinted, and quickly established these aspects of Santa in the popular imagination.

The poem was originally published anonymously; it was not until 1837 that Moore claimed authorship. He stated that the elements added to Santa were inspired by stories told by his Dutch gardener, and his friend and fellow writer Washington Irving (author of ‘Sleepy Hollow’).

Some people still dispute that Moore was the author.

Santa’s home at the North Pole was the invention of cartoonist Thomas Nast.

Nast was a political cartoonist, whose work regularly featured in ‘Harper’s Weekly’. For twenty years, between 1863 and 1886, he also supplied the magazine with Christmas drawings.

In his seasonal cartoon for 1866, Nast depicted Santa engaged in a variety of activities: making toys, decorating a tree, riding in his sleigh. In the margins of the image (barely visible above) is the label, ‘Santaclausville, N.P’.

The NP stood for ‘North Pole’, the first known time that Santa was depicted living there.

Several well publicised Artic explorations had occurred in the 1840s and 50s, this may have supplied Nast with his inspiration; an exotic, out-of-the-way location, where Santa could operate without being observed.