The world’s first video store opened in West Hollywood in 1977. It was the brainchild of a failed actor and former stuntman who would change the entertainment industry.

Video players are one of those inventions that are older than you think: the first was demonstrated in Berlin, in 1961 (for more inventions that are older than you think, see this list). Sony followed suit, and produced its first model in the US, in 1965.

These early players were quite different to their later incarnations.

They were bulkier, and looked more like a piece of stereo equipment; programs were recorded on large, open spools of magnetic tape. They were also expensive: Sony’s model retailed for $995 (equivalent to $9 200 today), and a one hour tape cost $60.

Their functionality was simple; you could record an hour’s worth of TV, and then re-watch it at your leisure.

Sony also pioneered the use of video cassettes, which they unveiled in 1972.

These were easier to use and more durable, and provided an expanded run time of 2 hours. This meant they could be used not just for recording, but to present feature length films.

Until this point, to see a movie you had to go to the cinema, or hope it popped up on TV; now they would be available anytime, at home.

American company Avco was the first to try retailing films in the new format. In 1972 they launched ‘Cartrivision’, a colour TV set with a connected video player, compatible with the company’s own square shaped cassette tapes.

Avco purchased the rights to 200 films which they offered for rent. The catalogue focussed on older classics, like ‘Casablanca’, ‘It Happened One Night’ and ‘Red River’.

The department store Sears sold the Cartrivision sets, and rented the tapes. Film rentals cost $3 to $6 per night, and each movie could only be watched once; the videos were designed so that they could not be rewound at home, but had to be returned and reset on a special device.

Cartrivision was a system ahead of its time; the high cost of the equipment meant that not many were sold. Avco discontinued the product after only 18 months.

But home video players did slowly grow in popularity, aided by improved technology; Sony launched their ‘Betamax’ system in 1975, and JVC the ‘VHS’ format in 1977.

Both offered improved picture and sound quality. VHS tapes also came in a 4 hour version which boosted sales in the US: it was perfect for recording games of American football.

The two companies waged war over potential consumers, as they sought to make their system the industry standard.

As more video players made their way into American homes, the idea of offering movies on video resurfaced.

Andre Blay was a Michigan businessman, who saw an opportunity in the expanding video market.

In 1977 he convinced Fox Studios to license 50 of its movies to his company, Magnetic Video. The films, which included more recent hits like ‘Patton’, ‘Planet of the Apes’ and ‘The Sound of Music’, would be made available in VHS and Beta, and sold via mail order.

The cost remained high. Blay charged $50 per film (equivalent to $240 present day), on top of which people would need to pay a $10 subscription fee to join the ‘Video Club of America’, required to purchase tapes.

In October 1977, Blay took out an ad for his new service in the popular ‘TV Guide’ magazine, which cost him $65 000. He received 9 000 responses, all stumping up the $10 fee; before he sold a single tape, he had paid for his ad and turned a tidy profit.

The strong response showed how popular video players had become in the previous 5 years. While Cartrivision had struggled to find customers, Blay was swamped, and faced difficulty keeping up with demand.

The movie studios took note, and slowly began to move into the video market themselves. Similar to Blay, their assumption was that people would want to buy copies of their films.

Someone else who noticed Blay’s success was George Atkinson, a small business owner based in Los Angeles.

Atkinson came from a colourful background.

He was born in 1935 in Shanghai, to an English father and Russian mother. During World War II they spent two years in a Japanese internment camp, when the war was over the family relocated to Canada, and then California.

Atkinson studied English literature at UCLA, and after graduating had a stint in the Army.

But his real passion was movies. He initially tried to make it as an actor, and in the 1960s had small roles in several TV shows. Later he would turn his hand to stunt work.

He never got his big break.

In the 1970s, Atkinson gave up on performing and opened a store on Wiltshire Boulevarde, renting out Super 8 cameras and projection equipment. He also carried a small collection of Super 8 films, which were mostly public domain titles aimed at children.

These were popular at birthday parties. Atkinson would later call it, ‘a micky mouse operation’.

Atkinson saw Blay’s ad, and paid his $10 to register. He would later purchase an entire set of Blay’s movies, one each on VHS and Beta.

Rather than buying the films for himself, Atkinson intended to make them part of his business, by offering them for overnight rental. He already rented out expensive camera equipment to people who could not afford to buy it, so why not movies?

To raise capital, Atkinson copied Blay’s idea of asking his customers for a subscription fee. They would pay a membership fee of $50 annually, or $100 for a lifetime, after which they could rent movies for $10 a night.

Despite the fact that video players were still found in less than 3% of households, the response was dramatic. When Atkinson placed a small ad in the LA Times promoting his new service, more than 1 000 people registered in advance.

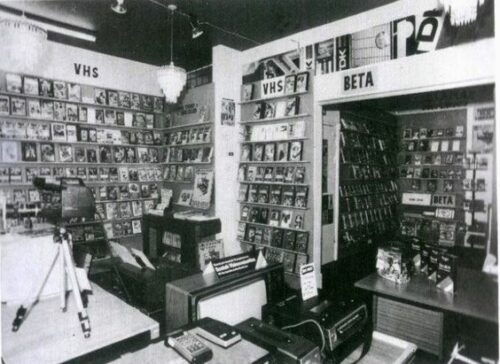

In late 1977, Atkinson cleared out half of his shop, renamed it ‘Video Station’, and put his tapes on display. It was an instant success.

A flood of customers signed up as new Video Station members. The store phone rang off the hook, and Atkinson had difficulty keeping tapes in stock.

Many of his new customers simply offered to buy the films outright:

‘They were your Cadillac and Mercedes crowd who would take 10, 15, 20 movies at a crack. They wanted to buy the videos rather than rent them, but the long-term future of the business was in rentals, not sales.’

– George Atkinson, interviewed in the LA Times

Atkinson would sell tapes to customers who were insistent, but he largely stuck to his rental model. And rented movies quickly made up the bulk of his revenue.

Video Station was so successful that Atkinson was able to open a second store just a few months later. A year later, he was selling them as franchises.

But his success also brought unwanted attention.

In 1978, the major movie studios threatened Video Station with legal action, claiming a violation of their copyright. Their concern ran deeper: they saw rented videos as a threat to their revenue, and tried to stop the practice before it caught on.

While Atkinson sought legal advice, he briefly changed his operating model. For a period his customers would ‘buy’ his tapes, but then have most of their money refunded, when they returned them.

But Atkinson was quickly assured that his legal position was secure. The ‘First-Sale Doctrine’ of American law allows vendors to resell or rent most copyrighted or trademarked materials, as long as the materials were legally purchased in the first instance.

It is this doctrine that allows other rental businesses, and second hand sellers, to operate. Video rental libraries were included in its legal protection.

The movie studios retreated from their threatened action against Video Station, and turned to having the First-Sale Doctrine changed instead.

In 1981, the studios lobbied Congress to have video rentals removed from the doctrine, similar to how recorded music had been excluded. Records, and later CDs, were not allowed to be rented, due to the ease with which copies could be made.

The studios argued the same should apply to movie rentals.

Atkinson, and the growing number of video store owners, formed the Video Software Dealers Association (VSDA) to fight the change. Faced with the growing popularity of the video rental market, Congress decided to leave the doctrine unchanged.

Through the early 1980s, Video Station continued to boom.

Cheaper video players meant the market expanded rapidly; from 3% of households in 1980, they were found in 20% by 1983. By the end of the decade, they were close to ubiquitous.

The demand for video content grew alongside, expanding from feature films to TV shows, and recordings of live events.

In 1983, Atkinson took Video Station public.

Listing on the stock market made Atkinson instantly wealthy, and he was appointed chairman of the company’s board of directors. But public companies have regulatory oversight, and in the same year Atkinson was accused of illegally overstating its profits.

He was eventually charged with filing false financial reports, and sentenced to five years’ probation.

His legal problems cost him his position, and he was forced to resign as chairman. Atkinson’s brother Edward, the company Treasurer, fared even worse: convicted of securities fraud, he would spend five years in jail.

Atkinson would stay on at Video Station as a consultant, and the business continued to expand. It was the first major video rental chain; at its height, it had 600 outlets across America and Canada.

George Atkinson died in March 2005, of complications related to emphysema. He was 69.

Proud of his achievements as a video rental pioneer, he told the LA Times that his only regret was, ‘that I didn’t patent it.’

At the time of Atkinson’s death, movies rentals, with DVDs replacing videos, were still a huge business. In 2005 there were more than 24 000 stores across the United States, generating $8 billion in annual revenue.

An offshoot of the movie rental market was ‘Netflix’, which had launched in 1997. Netflix began much as Andre Blay had done: offering DVDs for rent through the mail.

The company started slowly, but eventually grew into a major player in the movie rental market.

In 2007, aided by improvements to broadband internet, Netflix launched a streaming service, providing films online. This part of the company grew rapidly; in 2009, online streams overtook mail order movies for the first time, and soon left them far behind.

The online success of Netflix inspired imitators, who launched rival streaming services. Movie rental stores were in trouble.

In March 2017, the last of Video Station’s 600 outlets closed. The store, in Boulder, Colorado, had opened in 1982; the popularity of streaming, and rising rental costs, had finally done it in.

A group of long term customers gathered for the final day. Some of them wondered who would show them how to rent movies online, others just lamented the end of a store they had frequented since they were children.

‘What am I going to do without you? You’re my village. You raised me.’

– Virginia Detweiler, Video Station customer

Manager Dave Shamma, 69, put out a sign, thanking the loyalists. He would be retiring.

Asked what he would do with the store’s enormous inventory of 43 000 movies, he said, ‘I’m putting them in storage.’

Movie rental outlets suffered through the 2010s, and only a small number reached the end of the decade. Blockbuster, the largest chain and an icon of the 1990s, was reduced to a single store; it still operates in Bend, Oregon.

But in recent times, there have been reports that movie rental stores, even videos, may be making a comeback.

Their return is driven by nostalgia for old technology, and a desire for a more personal retail experience. Video stores, with a stock of hard to find movies and knowledgeable staff who can make canny recommendations, appeal to some people tired of content delivered to via a faceless, revenue focussed algorithm.

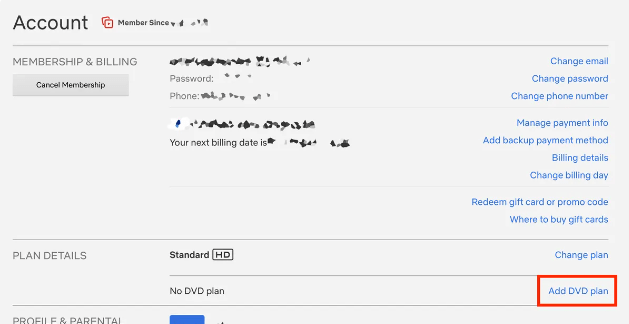

Even Netflix did not abandon their original business completely. Inside the United States you can still rent mail order DVDs, via an option on the ‘Account’ page.

Hello, I don’t know if this is still open, but if the writer/researcher of this article is still here I’d like to know if there are any resources I could be pointed towards. Specifically, the other avenues in which the larger industries at the time tried to penalize video stores through censorship and subsequently how this censorship backfired and turned into more profits for the video industry at the time.

Anyways, was a great read, I enjoyed it.