A fixture at get-togethers in Australia and New Zealand, and claimed by both, this humble sweet remains a cause of ongoing debate: who invented the Pavlova?

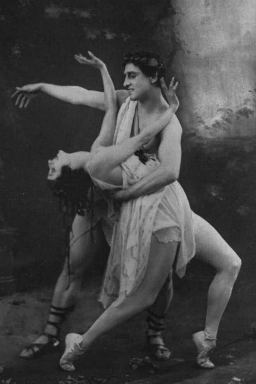

Our story begins with a dancer.

Anna Pavlova is one of history’s most famous performers.

Born in St Petersburg, in 1881, she was a sickly child, sent to live with her grandmother on the outskirts of the city. But it was her mother who introduced her to ballet: taking her to see a performance of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ when she was a child, at St Petersburg’s lavish Maryinsky Theatre.

Pavlova was inspired to become a dancer herself, and auditioned for the Imperial Ballet School when she was nine. Initially rejected, she was accepted the following year.

Classical ballet did not come easily to Pavlova.

She struggled to master the standard steps, and her personal style leaned away from formalism into something more impressionistic. But she also had a fierce work ethic. With relentless extra practice, often before and after the school’s ballet lessons, she steadily improved.

She graduated from the ballet school in 1899, aged 18, and then entered the Imperial Ballet’s dance company, then based in the same Maryinsky Theatre that had inspired her as a child.

Pavlova became a favourite of Marius Petipa, an influential choreographer and one of the ballet’s directors.

Petipa was a traditionalist, who favoured conventional interpretations of classic routines. While this seemed at odds with Pavlova’s style, the combination proved compelling: audiences responded to her passionate performances within a formal framework.

Pavlova was so focussed on her performance she frequently became caught up in the moment; in one famous example she was so swept away, she danced right off the stage and fell into the audience.

By 1901, she was the lead dancer in the company.

In 1905, Pavlova commissioned a new piece called ‘The Dying Swan’, from choreographer Michel Fokine.

Pavlova was an animal lover, with a particular fondness for birds. She had become fascinated by the swans she saw in St Petersburg’s public parks, and thought them a good subject.

The new ballet, running only four minutes, would become her signature routine.

Pavlova first performed ‘The Dying Swan’ at a gala in December 1907. It showcased her strengths, combining dramatic arm and upper body movements, less footwork (not her strength), capped with an emotional crescendo as the swan’s life comes to an end.

It was instantly a smash, the talk of the town. Pavlova would eventually perform the dance more than 4 000 times.

In 1910, Pavlova formed her own dance company.

This was a bold move for the era; ballet was dominated by large, well-known companies, and a woman taking such direct control over her career was unusual:

‘(This was) a very enterprising and daring act. She travelled everywhere in the world that travel was possible, and introduced the ballet to millions who had never seen any form of Western dancing.’

– Agnes de Mille, ‘The Book of Dance’

Based in England, Pavlova took her company around Europe, and then the world. She was particularly popular in America; she first visited in 1912, and returned almost annually thereafter.

Her reputation grew, and enormous crowds turned out to see her perform, wherever she appeared. Pavlova became a global celebrity, when this idea was still new.

In 1926, she embarked on her first tour of Australia.

Pavlova arrived in Melbourne in March 1926, with her entourage and a company of 45 dancers.

Performing ‘The Dying Swan’ and a suite of other routines, the tour started with four weeks of performances at Her Majesty’s theatre, on Exhibition Street. Excitement for Pavlova’s appearances had been steadily building, and the season sold out quickly.

The reviews for her dancing were rhapsodic:

‘Pavlova’s admirers have thrown their hearts between her twinkling feet. Every appearance of the great dancer has brought hundreds more under the spell of her wonderful personality.

Her genius permits her to transmit from the stage to the spectators the exhilaration which springs from the emotions of her dance, so that the pleasure is rightfully shared by dancer and spectator.’

– Review in ‘The Argus’, March 22, 1926

In her free time, Pavlova enjoyed walking in the city’s public parks, delighted to find swans living in the lakes. She even managed several side trips to the Dandenong Ranges, where she went hiking and bird watching.

Having endeared herself to the city, Pavlova’s final appearance in Melbourne was on 13 April. The crowd threw paper streamers and flowers, that entirely covered the stage.

Pavlova’s company then moved on to a month of dates in Sydney, after which the tour continued in New Zealand and then Brisbane. Everywhere they played to full houses, and rave reviews.

The tour was an enormous financial success, generating more box office revenue than any previous performer’s tour to Australia.

Cashing in on Pavlova’s popularity, a wide variety of products used her likeness. There were commemorative items and souvenirs of the tour, but everyday brands and companies also tried to take advantage:

‘Pavlova’s name and portrait were used to advertise all sorts of products including shoes, hosiery, hire-cars, confectionery and beauty products. The music retailer Paling’s was one of many companies who used her name and portrait for promotional advertisements.’

– Ausdance, ‘Pavlova’s 1926 Australian tour’

Pavlova was not compensated for most of these promotions.

The tour ended with a series of dates in Adelaide.

In August, after five months of near continuous appearances, the exhausted company set sail for England. Pavlova took a cage of native Australian birds with her, to add to her private aviary. Subsequently, Pavlova continued to dance and tour, returning to Australia in 1929.

She died in 1932, aged only 50.

A ‘pavlova’ is a desert made of meringue and cream, topped with fruit, its simple recipe coming in endless variations.

While it is now viewed as a bit old fashioned, it remains popular in both Australia and New Zealand, and is often a feature at barbecues, or summer get togethers. Both countries claim it as their own creation, the debate over its origin has been ongoing for some time.

One thing that locals usually agree on: it was created, and named, as a tribute to Anna Pavlova, part of the impact she had when she toured.

Herbert ‘Bert’ Sachse was a chef at Perth’s ‘Esplanade Hotel’ in the 1930s.

In 1935 the owner, Elsie Ploughman, asked Sachse to come up with a new desert. The hotel already sold meringues, egg whites that are sweetened, whipped and baked, which were a popular desert at the time. But Ploughman wanted something new.

‘The meringue cake was invariably too hard and crusty, so I set out to create something that would have a crunchy top and would cut like a marshmallow. After a month of experimentation – and many failures – I hit upon the recipe, which survives today.’

– Bert Sachse, interviewed in 1973

Ploughman was very pleased with the outcome, and the new desert went on sale. The name came from the hotel’s manager, who tried it and supposedly quipped that it was, ‘as light as Pavlova.’

But 1935 is some years after Pavlova’s last tour of Australia. If inspired by her, could the desert have originated closer to her actual appearances?

Professor Helen Leach, an expert in food anthropology at the University of Otago, in New Zealand, decided to find out. And she would uncover evidence of three different deserts, that predated Sachse’s creation.

From 1926 there was a layered, multi coloured jelly dish, that was also known in Australia. From 1928 there were small, walnut flavoured meringues, a snack, that originated in Dunedin. And in 1929, a large, fruit and meringue cake, that appeared in a regional cooking annual.

All three of these were called ‘Pavlovas’. The last, in particular, closely resembled the modern incarnation of the dish, which seemed to move its origin across the Tasman.

Leach thought so, and wrote a book about her investigation, called ‘The Pavlova Story: A Slice of New Zealand’s Culinary History’.

But what if a more radical version of history were available? Is it possible, that Pavlovas do not originate from Australia or New Zealand?

Meringues were an 18th century invention, credited to a Swiss pastry cook named Gasparini. They were originally baked as small, edible goodies, often called ‘kisses’, that could be eaten as a snack or added to other deserts.

Their versatility was part of their popularity; meringues were easy to make, and could be utilised in cooking in a variety of ways.

Culinary historians Dr Andrew Paul Wood and Annabelle Utrecht (the former a kiwi, the latter Australian) have also researched the history of Pavlovas, which they trace to this period.

In Austria, meringues were baked in large discs which were arranged in layers, separated by cream and fruit.

Known as a Spanische Windtorte (AKA: souffle cake), this dish was particularly popular with the Hapsburg rulers, of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

In neighbouring Germany, this recipe evolved into a similar meringue based cake, known as ‘Schaum Torte’. This did away with the layers, and moved the fruit to the top, and proved widely popular.

By the early 1800s, ‘Schaum Torte’ had spread through Europe, and even across the Atlantic, brought by waves of migrants.

‘By 1860 you can find it in Great Britain, Russia and North America. I have made a couple of cakes from 1850 that I have served to guests and asked what it was, they say pavlova. But I tell them it’s not, it’s a Schaum Torte.’

– Annabelle Utrecht

Schaum Torte continued to spread into the 20th century. It arrived in Australia with German immigrants, sometime between the two world wars.

Wood and Utrecht think it was a recipe for this dish, or something very similar to it, that inspired Bert Sachse in 1935.

Wood and Utrecht are working on a book, tracing the Pavlova’s European history. Their investigation also revealed hundreds of other recipes, for a variety of dishes all over the world, named after Anna Pavlova.

This is a story i grew up with because my mum was an apprentice to Bert Sachse at the Esplanade Hotel in Perth for five years from the late 1930’s.

Not surprising that she had no doubt Bert was the inventor.👍

Thank you for sharing that! I think he has a very strong claim as the inventor.